Read all about it at The Washington Monthly, 20,000 Leagues Under the State.

Read all about it at The Washington Monthly, 20,000 Leagues Under the State.

A Personal Blog

by Michael Froomkin

Laurie Silvers & Mitchell Rubenstein Distinguished Professor of Law

University of Miami School of Law

My Publications | e-mail

All opinions on this blog are those of the author(s) and not their employer(s) unelss otherwise specified.

Who Reads Discourse.net?

Readers describe themselves.

Please join in.Reader Map

Recent Comments

- Michael on Robot Law II is Now Available! (In Hardback)

- Mulalira Faisal Umar on Robot Law II is Now Available! (In Hardback)

- Michael on Vince Lago Campaign Has No Shame

- Just me on Vince Lago Campaign Has No Shame

- Jennifer Cummings on Are Coral Gables Police Cooperating with ICE?

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Join 51 other subscribers

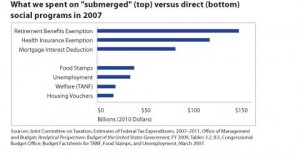

From the article:

“Understandably, to many people tax breaks may seem substantively different from traditional social benefits. The latter are funded by tax revenues collected from the public and delivered through checks or services to particular citizens, whereas tax breaks function by allowing recipients themselves simply to keep more money, reducing the amount that they would otherwise owe”

I agree, and the substantive differences go further. While there is certainly room for abuse by special interests, targeted tax breaks create incentives for behavior and choices deemed socially beneficial. In order to get the mortgage interest deduction, for example, you must incur risk and expense of becoming a homeowner. In order to get a rebate for buying a green appliance, you have to go out and buy it with your own money.

Thus, while the article is correct that from an accounting standpoint a tax cut is identical to a traditional welfare expense, this is not true from an economics standpoint. A tax cut incentivizes behaviors that we hope will result in less expenses, i.e., tax rebates incentivize consumers buy green appliances so we don’t have to build a new power plant and/or burn less fossil fuels. Supposedly, neighborhoods with higher home ownership rates have lower crime and other social costs than neighborhoods with high rental rates, hence the mortgage interest deduction. Are there abuses of tax breaks, sure, and we should police them.

I will leave it your readers to discuss what traditional welfare incentivizes.

Personally, I am big believer in charity (unlike a certain vice president I know…). State sponsored welfare, not so much.

I’m afraid the following is not accurate:

To an economist a tax expenditure and a straight public subsidy (whether, a cash rebate on a purchase, or a subsidy to build a stadium) are the same regardless of what they are spent on. The distinction I think you are trying to draw is between the government subsidizing things where people shell out money (in effect, a form of co-payment), and straight transfer payments, where the government just gives people money to live on. (But where does the stadium fit in there?) If we did welfare by tax rebates (assuming that there were taxes to rebate), an economist would not distinguish it from the transfer of cash. But of course there are usually not sufficient taxes to rebate, so the issue doesn’t arise — except in the case of the earned income credit. Which precisely proves my point.

It is possible to argue that transfer programs risk incentivizing undesirable behavior (e.g. people choosing not to work due the incredible generosity of welfare payments), but real-life examples of these behaviors seem thin on the ground.

We agree in principle but not semantics. To an accountant, whether you spend $1B or take in $1B less in revenue, the result is the same and his analysis ends there. The economist, on the other hand, agrees but also looks a “few moves ahead.”

Will the $1B entitlement expense create greater cost savings, or increased revenue down the road? Same question, but for the tax rebate?

If we offer a $1B rebate to consumers who purchase green appliances, and as a result spend $5B less next year in public costs of energy creation (or have $5B worth of cleaner air, etc., …), then we didn’t really loose $1B (the accountant’s view), we had economic gain of $4B (the economist’s view). In other words, tax incentives are a form of investment.

The same analysis *could* be applied to entitlements, but you’ll have a hard time convincing me that entitlements result in some sort of economic net gain, or that they constitute an investment. Granted, a few probably do, but most just create more external costs, in my opinion.

In any case, we agree the Marlins stadium is a boondoggle, that will never generate economic benefits comparable to what the public has spent on it. Although, I hope they prove us wrong. I agreed there are abuses of incentives (just as there are abuses of entitlements) which need to be policed.

I’m glad we agree that the form of expenditure (tax v. $$) is not economically relevant.

The other issues all go to what kind of return there is on the expenditure, ie what the medium/long-run economic effects are. Some expenditures are investments in physical capital, some in human capital, some are just consumption (e.g. buying a tank), although there may be good reasons (security) to make the expenditure. Each can also have multiplier effects on the economy, further complicating the economic issues.

“Entitlements” like welfare do at least two things: they preserve human capital, and they make a decent society. The return on both seems worth the expense to me. There do seem, however, to be a lot of people who put very low values on both.

Many so-called entitlements, however, have a different aspect, being more a delayed quasi-contractual payment (e.g. veterans’ benefits, medicare and social security payments) in which people who have earned a benefit from their past activities now receive it.

““Entitlements” like welfare do at least two things: they preserve human capital, and they make a decent society. The return on both seems worth the expense to me. There do seem, however, to be a lot of people who put very low values on both.”

I disagree that a lot of people put low values on both. Most Americans are extremely charitable and generous given an opportunity. The fact that they do not believe the government should run a charity does not mean they do not believe in charity.

I find it ironic (and pathetic) that populist politicians like Biden are relatively stingy when it comes to charity, yet state that it is “patriotic” to pay taxes which fund, in part, the government run charity.

Why is it odd or pathetic to prefer solutions to important social issues that deal straightforwardly with the collective action problems? It seems sensible to me.

We have a fundamental disagreement as to whether the government does anything straightforwardly.

Perhaps. But the difference may also be that I take the attitude of “compared to what” and often am not any more impressed by the private sector. Banks. Health insurers. Auto makers. And then there are the externalities…

There are of course great companies out there, doing well and doing good. But I think they are less common than myth suggests. And certainly not inevitable.