Because Coral Gables does not have run-off elections, there is always a risk in multi-candidate Commission elections that a person might elected with less than a majority vote. Indeed, this has happened more than once in recent memory, with the most recent case being now-Commissioner Slesnick who was elected with 32% of the vote in a six-candidate race.

A run-off, however, would be expensive, and also risks declining voter participation. Voter participation is already low enough in the April off-year election. One solution would be to move the election to the ordinary primary date in August, and have any necessary run-off in November. I have detected very little appetite for this among Commissioners and other movers and shakers in the Gables. The reasons vary. Some people think that too many people are on vacation in August. Others think that too people who don’t care much about local government would vote (the polite term for this is ‘fear of low-information voters’). Still others think that the non-partisan character of the race would be overrun with the partisan fervor of the regular election. And yet others fear that come November UM students would have too much sway. I don’t agree with most of these views, but they’re out there.

Fortunately, there a solution to the problem of running a fair multi-candidate election that produces a majority winner without having to change the election date or having a second, runoff, election. The solution is to switch from the current first-past-the-post voting system to Single Transferable Vote (STV), also known as Instant Runoff Voting.

With the very able help of my research assistant, Steven Strickland, I’ve written a memo which outlines some of the advantages of using STV and sent it to each of the five members of the Coral Gables Commission. I hope that Coral Gables will consider changing to STV for future elections to ensure that our elected officials have the support of the majority of the electorate, and are seen to have that support.

The text of our memo, reformatted to make it more web-friendly, is below.

MEMORANDUM

TO: Coral Gables Commission

FROM: Professor A. Michael Froomkin & Steve Strickland

RE: Single Transferable Vote Elections

DATE: April 21, 2015

Summary

- In a Single Transferable Vote (STV) election, voters rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate earns a majority of first-place votes, the weakest candidates are successively eliminated and their votes are added to the totals of the voters’ next preferred choices until a candidate receives a majority of first-place votes.

- Unlike the current voting system in Coral Gables, an STV election system eliminates the possibility of a candidate being elected with a minority of votes and does not discourage voters from voting for their preferred candidate for fear of wasting their vote.

- The STV system is used in many U.S. municipal elections, including San Francisco, Minneapolis, and Memphis.

- Other than the cost of any required software updates, holding STV elections in Coral Gables should not cost much more than the current voting system because Miami-Dade County uses a model of optical scanning machines to count votes that has been successfully used for STV elections in other cities, and STV elections eliminate the need to hold runoff elections.

I. Single Transferable Vote (STV) Elections

In a Single Transferable Vote (STV) election, also known as instant-runoff voting and ranked-choice voting, voters rank candidates in order of preference (first, second, third, and so on). STV eliminates the possibility of a candidate being elected with a minority of votes, without forcing the city to hold a second, separate runoff election. Moreover, unlike in Coral Gables’ current voting system, in an STV election, no one would be afraid to vote for his true first choice for fear of wasting a vote on an unlikely winner when there is no runoff election. 1

STV in Single-Seat Elections

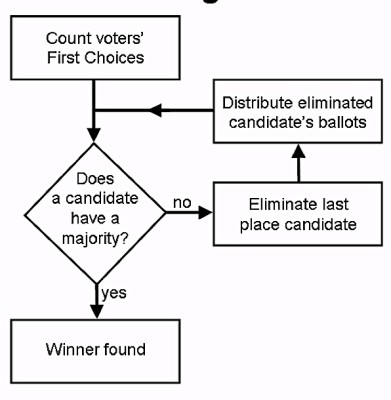

After the ballots are counted, if no candidate earns a majority of first-place votes, the candidate who receives the fewest first-place votes is eliminated. The ballots are then recounted, with each ballot counting as one vote for each voter’s highest ranked candidate who has not been eliminated. Voters who initially chose the now-eliminated candidate will have their ballots added to the totals of their second ranked candidate––just as if they were voting in a traditional two-round runoff election––but all other voters get to continue supporting their top candidate who remains in the race. Until a candidate receives a majority of the votes and is declared the winner, the weakest candidates are successively eliminated and their voters’ ballots are added to the totals of their next preferred choices.

Here is a diagram of a sample STV transfer process in a single-seat election.

STV in Multiple-Seat Elections

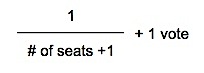

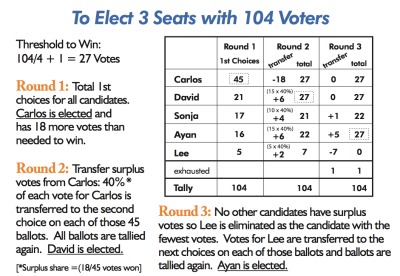

In a multi-seat election, voters vote in the same way as in a single-seat election – ranking all the candidates in order of preference – but the votes are counted slightly differently. The exact method of redistributing votes for a multi-seat election may vary, but a typical method is as follows: If a candidate receives a certain threshold share of votes, they will be elected. Typically, the threshold is determined by dividing the total number of voters by the number of seats plus 1, then adding one vote). After a candidate is elected, the software calculates the number of “surplus” votes that the elected candidate earned over the required threshold amount of votes needed to win. This “surplus” vote number then sets the discount rate (“surplus” votes for winner divided by total votes for winner) used when the votes cast for the already-elected candidate are then proportionally transferred to those voters’ second choice candidates. This way, no one is penalized having voted for a very popular candidate. (See example below.) A very good illustrations of the process, produced by Minnesota Public Radio, can also be found on YouTube.

After a candidate is elected, the software calculates the number of “surplus” votes that the elected candidate earned over the required threshold amount of votes needed to win. This “surplus” vote number then sets the discount rate (“surplus” votes for winner divided by total votes for winner) used when the votes cast for the already-elected candidate are then proportionally transferred to those voters’ second choice candidates. This way, no one is penalized having voted for a very popular candidate. (See example below.) A very good illustrations of the process, produced by Minnesota Public Radio, can also be found on YouTube.

If no second candidate has reached the threshold after the discounted second-choice votes are reapportioned, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. The voters who selected the defeated candidate as their first choice will then have their votes counted for their second choice. This elimination process continues until every seat is filled. 2

Here is an example of a sample STV transfer process in a multiple-seat election: 3

The mechanics of the STV process are the same regardless of how many candidates the voter ranks, and how many are left unsorted. 4 If a single ballot has all of its ranked candidates eliminated, it is ‘exhausted’ and is set aside rather than counted for any candidate. The exhausted ballot would still count for the threshold amount to get elected though because the threshold amount is based on the total number of votes cast.

Assuming no other change to Coral Gables’ current voting system, STV would be used to pick a single winner from each Commission candidate Group (see “STV in Single-Seat Elections” above).

If, however, Coral Gables were to decide to eliminate Group-based voting, STV could also be used to pick the top two winners for four-year Commission seats from a single candidate pool. Presumably, as the Mayor’s office is distinct and has a different term, the Mayor’s race would always be a one-seat race. Coral Gables could, however, choose to pool the other two Commission seats in contention every year into a single STV race. (see “STV in Multiple-Seat Elections” above).

Pooling has the advantage of eliminating the strategic element in which candidates must select which of the two formally identical Groups to contest. In the most recent election, for example, the large majority of the candidates running chose to contest Group V, leaving the Group IV race with fewer candidates. A pooled system is also arguably fairer, as all candidates contest for all the available seats on a more equal basis. Additionally, a pooled election removes the risk that some voters may be frustrated when they are forced to choose between two candidates that they like in one race, while in another they disapprove of all of the candidates. 5

A non-pooled election, on the other hand, has the virtue of familiarity, as voters and current office-holders are accustomed to the current voting system. Moreover, a non-pooled election encourages civility and cooperation among office-holders because incumbent office-holders will not be required to run against one another. A related disadvantage of non-pooled elections, however, is that they favor incumbents, which limits both accountability for office holders and potential challengers’ opportunities for public service.

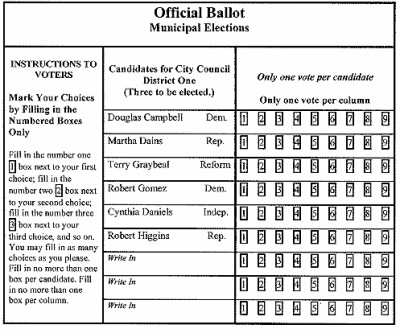

Whether pooled or non-pooled, the only substantial downside of STV is that voters must fill out a slightly more complicated ballot. As the following example shows, however, it is possible to design a ballot that is self-explanatory: 6

II. Use of STV in United States

Single transferable vote systems are used in municipal elections in the United States in San Francisco, California; Minneapolis, Minnesota; St. Paul, Minnesota; Oakland, California; Berkeley, California; Portland, Maine; Telluride, Colorado; Memphis, Tennessee; and Santa Fe, New Mexico. 7 The City of London, England also uses STV for its mayoral elections. 8 Furthermore, more than 50 universities in the United States use STV for student elections, including Harvard University, Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the California Institute of Technology. 9

III. Cost of STV

STV elections are much cheaper than having a separate runoff because they function just like a two-round runoff election. 10

Holding an STV municipal election in Coral Gables should not impose significant extra costs above the current Commission election because Miami-Dade County uses optical scanners to count ballots. 11 The DS200 optical scanner used in Miami-Dade County is also federally certified and has already been successfully used for STV elections in other cities, such as Minneapolis, Minnesota. 12 In addition to whatever the vendor might charge for new software, the only costs attributable to a switch in voting systems should be a need for equipment testing, voter education materials, and election worker training programs. However, as the YouTube video cited above demonstrates, many such materials are already available.

- How Instant Runoff Voting Works, FairVote (2014).[↩]

- How Ranked Choice Voting Works in Multi-Seat Elections, FairVote MN; Counting multiple seat office elections, FairVote MN; Ranked Choice Voting/Instant Runoff Voting, FairVote (2014). For a video explanation of the STV process in a multi-seat election, see Minnesota Public Radio, How Instant Runoff Voting works 2.0: Multiple Winners, Youtube (2009).[↩]

- How Ranked Choice Voting Works in Multi-Seat Elections, FairVote MN.[↩]

- Instant-runoff voting, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII (2010).[↩]

- City Council Election Methods, FAIRVOTE 10.[↩]

- Douglas J. Amy, Proportional Representation Voting Systems, MT. HOLYOKE COLLEGE (2006).[↩]

- Where Ranked Choice Voting is Used, FAIRVOTE (2014).[↩]

- Where Ranked Choice Voting is Used, FAIRVOTE (2014).[↩]

- Colleges and Universities Using Ranked Choice Voting, FAIRVOTE (2014).[↩]

- Instant Runoff Voting FAQ, FAIRVOTE (2014).[↩]

- 2014 Voting Systems, FLORIDA DIVISION OF ELECTIONS (2014); IRV Resources, FAIRVOTE (2014).[↩]

- Minneapolis Instant Runoff Voting FAQ, FAIRVOTE MINNESOTA (2008); Curtis Gilbert, IRV poses few problems for Minneapolis voters, MPR NEWS (Nov. 3, 2009).[↩]