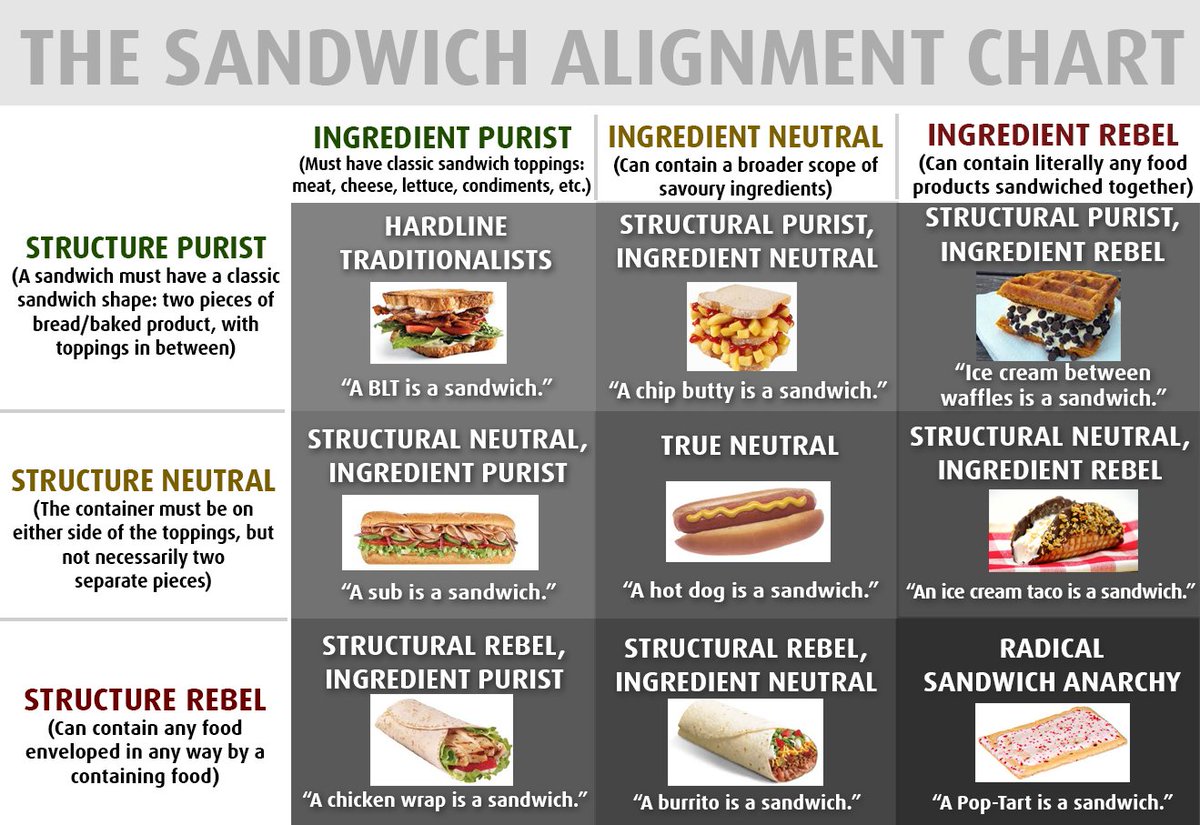

I think I could teach a terrific law class around the sandwich alignment chart. Students so often underrate the problem of assigning meaning to (or deriving meaning from) words.

For what it’s worth, temperamentally I seem to be mostly an ingredient purist, except that I would count a burrito as a sandwich. I might count myself as more ingredient neutral, in that a chip butty does look like a sandwich, except that they are so disgusting no one should eat one.

I should also note that there is actually a case about this exact issue, White City Shopping Center, LP v. PR Restaurants, LLC, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 565 (Massachusetts Superior Court for Worcester County, 2006). There was a shopping mall agreement that allowed a Panera Bread franchise to object to the opening of businesses in the mall “that primarily sell sandwiches”. The issue was whether a Qdoba, makers of burritos and tacos, was caught by that provision. Judge Jeffery Locke held that–at least as regards the interpretation of that contract–a burrito was not a sandwich. For more on the issue see Marjorie Florestal, Is a Burrito a Sandwich? Exploring Race, Class and Culture in Contracts, 14 Mich. J. Race & Law 1 (2008).

Some people think words have absolute meanings. Others think they are cultural. I tend to the cultural, but recognize that some legal documents, like contracts, should be interpreted to fix a meaning in a time and place. The hard question is to what extent our Constitution does that, and to what extent either its framers, ratifiers, or inheritors rightly treat those meanings as evolving over time.