Judge John F. Grady c. 2014

Judge John F. Grady of the Northern District of Illinois died on Monday at the age of 90. I had the privilege of clerking for then-Chief Judge Grady just after graduating from law school in 1987. In his chambers and in his court room I saw the best that the U.S. legal system has to offer.

Judge Grady had a number of defining qualities, including fairness, decency, intelligence, and a deeply rooted sense of right and wrong. He was a very smart man; unlike a lot of the people you meet on law faculties his intellect focused primarily on things with practical payoffs. He put that bent to good use not just in the courthouse but in state and national rule-writing projects for which he was drafted, not least as Chairman of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. He had acquired a national reputation as a good judge by the time I clerked for him, although not as the sort of ‘feeder’ judge whose clerks went on to the Supreme Court or the academy. In part this was because the very large majority of the Judge’s clerks graduated from Chicago law schools, especially Northwestern of which he was very fond, and wanted to stay in Chicago. I can see why: I learned to love Chicago and its neighborhoods, although not its winter winds nor, despite a delightful afternoon at Judge Grady’s annual trip to Wrigley Field with his clerks, the Cubs.

Judge Grady was not political; he was appointed in the Ford administration and his politics, at least as visible to his clerks, consisted mostly of a conviction that most people were capable of being good, everyone had a duty to be, and those who weren’t deserved (measured) sanctions. This view was reflected in Judge Grady’s enormous faith in juries.

Judge Grady was a product of the Chicago outskirts, not the city. As a former Assistant U.S. Attorney (AUSA) and then sole practitioner he had no particular love for big firms and especially their billing practices. We clerks thought his only fault as a judge was that he was both slow to decide and sometimes a bit harsh when it came to fee petitions. Judge Grady would only allow that he had a duty to be thorough. (One clerk joked to me that the Judge couldn’t see how anyone could fairly charge more than he would have 20 years earlier — which was a little unfair but close enough to be funny.) That said, Judge Grady’s “Order Concerning Format of Fee Petitions,” Cristancho v. Nat’l Broad. Co., 117 F.R.D. 609 (N.D. Ill. 1987), is a model of good sense. I’ve always been puzzled that it didn’t become a national standard.

Judge Grady was a courageous judge and an innovator. He allowed jurors to take notes back when that was unheard-of, and allowed jurors in civil trials to ask questions when that was almost heretical. He’d have allowed it in criminal trials too if only the lawyers would have agreed, but he told me regretfully that they never did.

Judge Grady was in most ways a humble man, and certainly very modest about his considerable achievements. I once asked him if he minded being reversed, and I believed him when he said it did not trouble him: he did his thing, the court of appeal or the Supreme Court did theirs, and he was fine with that, he just moved on.

That said, Judge Grady ran a tight ship in court. I will never forget a pretrial status conference in a long-running patent case (for some reason Judge Grady loved trying complicated patent cases) that was finally nearing trial. The attorneys had submitted their proposed witness lists and Judge Grady was reviewing them in order to determine how long the trial might be. “Who is Mr. [name]?” Judge Grady asked the lawyer for one of the parties. “Judge, that’s our law expert,” answered the advocate. “Law expert? There’s only one law expert in this court,” Judge Grady growled as he drew a line through that name on the printed list before him. And we never heard of that witness again. I learned much later that in state courts, perhaps especially in places like Florida where state court trial judges don’t have clerks to do research for them, it’s a routine practice in cases with uncommon legal issues to bring in a professor to testify as to the relevant law as a way of educating the judge, and the judges appreciate the practice. But not in federal court.

Judge Grady did his own research, or he asked us to do it and then personally checked anything that seemed the least bit debatable. For motion practice the Judge would read the papers and the leading cases and then tell us how he was “leaning” and ask us to write a draft opinion. The “leaning” almost always struck me as the right answer and I was proud that within a month I was able to write drafts that attracted at most minor corrections; the one or two times over the clerkship that the “leaning” seemed at odds with precedent, the judge asked me to provide the cases on which I based the contrary conclusion so he could mull them over. In one for-this-reason-only memorable technical case about jurisdiction in admiralty I even persuaded the Judge to adopt a view he had not considered, although he clearly thought the controlling precedents on the “saving to suitors” clause, 28 U.S.C. § 1333(1), were more than a bit weird. Certainly the lawyers, neither of whom had briefed the jurisdictional issue (lack of federal jurisdiction is a matter that federal courts may raise sua sponte) looked a bit pole-axed at the prospect of being sent to state court when he gave them the ruling from the bench. I thought he sympathized.

Judge Grady was no bleeding heart, and was not shy of the tough sentence when he thought it deserved. But he was also a very firm believer in defendants’ rights, and in the Bill of Rights in general. As Chief Judge he handled all grand jury matters, most of which were kept tightly under wraps and in which we law clerks were rarely involved. But one case raised an issue that did make it into open court. It seems the local cops (or the FBI, I forget) had raided an Asian gambling den, and handed out subpoenas to appear before the grand jury to everyone in the room. At the appointed time for one of the appearances, an Asian gentleman appeared before the jury and was asked by the AUSA to state his name. The gentleman refused, pleading the Fifth Amendment.

The AUSA sought an order compelling an answer to that initial question. The defendant’s lawyer argued that forcing the defendant to state his name would potentially incriminate him as tying the body present before the jury to the one served with the subpoena (or, I suppose, outing him as an impostor but if I recall that wasn’t argued). The AUSA replied that the name itself wasn’t incriminating, just a standard procedure to ensure the subpoena was being complied with, a matter for which the government was entitled to the Court’s assistance. One got the feeling, however, that for some reason (all Asians looked alike to Chicago cops?) if the government didn’t have the name, they’d be unable to prove that the person who turned up wasn’t the one named on the paper.

Unusually, Judge Grady asked both his clerks to work on the matter, and he didn’t tell us how he was ‘leaning’ so as, he said, not to prejudice us. We looked hard, but as I recall didn’t find a lot of law on the subject. What we did find seemed to lean somewhat in the direction of not compelling the person to testify. I confess that I feared that the Judge, who had been in the Criminal Division of the U.S. Attorney’s office himself, might not find this a congenial conclusion, and to be fair it didn’t seem exactly compelled by any decision we could find. To my surprise, the Judge adopted that view happily, saying it was what he’d been thinking. It wasn’t the Court’s job to do the prosecution’s work for it, that was part of what the Fifth Amendment was about. And so, to the AUSA’s poorly camouflaged shock and disgust, it was.

The Judge appreciated good lawyering and was saddened by shoddy work. As an experienced judge by the time I arrived, Judge Grady did not feel the need to have law clerks in court to be prepared to research issues for him and comfortably ruled on evidentiary issues from the bench. Generally the law clerks toiled in the back office, writing draft rulings on motions to dismiss and summary judgment motions, while the Judge held court. We emerged mostly on motion days and on the rare occasion when the Judge thought we might learn by watching a master lawyer at work. Thus it was that I got to see a cross-examination right out of the movies in which the defendant company’s lawyer destroyed the plaintiff company’s expert witness in a couple of hours of withering cross-examination. It was clear that the lawyer understood that facts (and the math!) better than the ‘expert’ who was reduced to a nearly incoherent wreck by the time it was mercifully over. The case settled shortly afterwards for a couple pennies on the dollar. (“They could have had that two years ago,” was the defense lawyer’s parting shot as he went out the door.) It was a valuable lesson in the value of preparation and, I later came to see, the need to stress test your experts.

Judge Grady taught primarily by example, and he taught well. I cannot think of anything I’ve done before or, sadly, since his clerkship that has given me more confidence in the U.S. legal system. A world where Judge Grady clones decided the cases as a matter of first instance — Judge Grady occasionally sat on courts of appeal by designation, but I gathered he much preferred trying cases on his own — might not be a perfect one, but it would be a lot better than the world we got.

The 7th Circuit Bar Association’s Journal did a good interview with Judge Grady in 2011, when he’d taken senior status after 39 (!) years on the bench, although he was still hearing cases until his retirement in 2014. The interview captures his voice, but since it is his voice it undersells his achievements.

I did not know this:

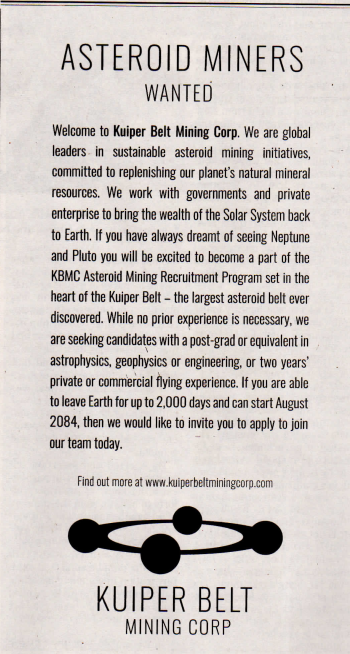

I did not know this: The enticing ad ran on the bottom right of page A9 of today’s New York Times.

The enticing ad ran on the bottom right of page A9 of today’s New York Times.